-40%

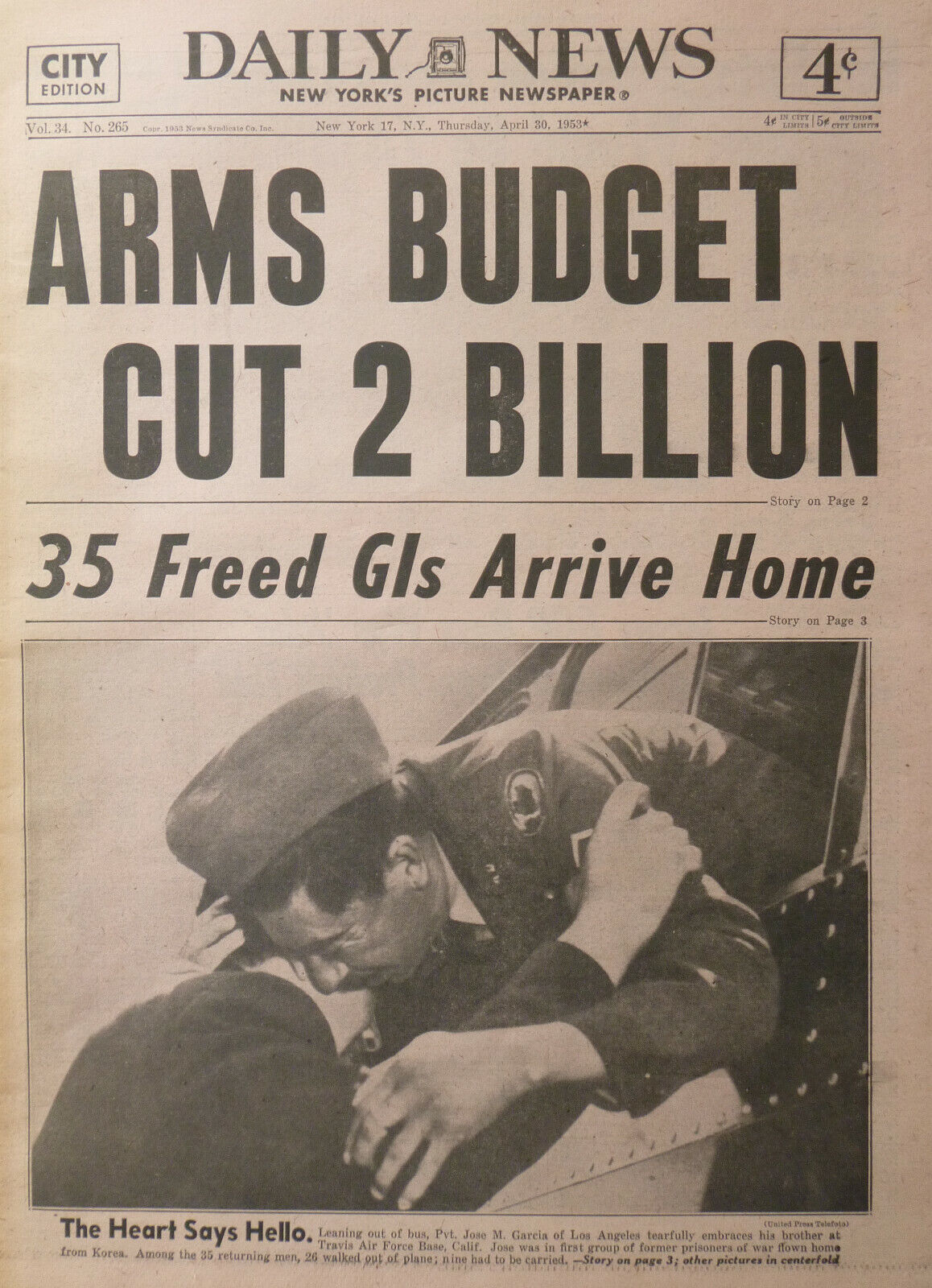

BRITAIN SINKS FRENCH NAVY IN ALGERIAN PORT ORAN JULY 4 1940 070107WQ B9

$ 42.23

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Original Paper Winnipeg Free Press July 4th 1940 (22 Pages)Operation Catapult was the name given to Britain’s attack on the naval fleet of France in July 1940. Operation Catapult was an attempt to ensure that the Germans did not get their hands on the six battleships and two battle-cruisers that the French had in their fleet.

The German attack on France had been staggeringly successful in the spring of 1940. After Dunkirk, the French made it clear that they were willing to sound out from the Germans terms of surrender. Britain gave its support to this but on one condition – that the French fleet had to sail to British harbours.

If Britain was to fight Germany alone, she needed to exploit to the full her naval supremacy. The fall of France would have given Germany the use of French Channel and French Atlantic ports which by the very nature of their geographic positions threatened the Royal Navy. If Germany was successful in the western Mediterranean Sea – especially as her ally Italy had entered the war on June 10 – then British naval supremacy in the Mediterranean as a whole would be threatened. Therefore, Britain had to do all it could to reduce this impact. Fearing that the Germans would take over and then use the French Navy, Britain requested that it should sail to Britain before the French surrender. Britain also feared the German takeover of her naval bases at Dakar and Mers el Kébir both of which could have been used to attack Allied convoys going around the African coastline to the Far East .

“Provided, but only provided, that the French fleet is sailed forthwith for British harbours pending negotiations, His Majesty’s Government give their full consent to an enquiry by the French government to ascertain the terms for an armistice for France.”

W Churchill

Many of the ships in the French Navy were modern in design though lacking in modern radar and sonar. Admiral of the Fleet Darlan had done a great deal to improve the efficiency and discipline found within the navy. The navy had played its part in the evacuation at Dunkirk and as the German Army marched west, the French Navy sailed for its African bases. A number of older ships had sailed for Plymouth and Portsmouth (two old battleships, three submarines and eight destroyers) but two modern battle-cruisers, six destroyers, two older battleships and a seaplane carrier docked at Mers el Kébir near Oran in Algeria. Six cruisers were based in Algiers and a number of ships were based in Alexandria in Egypt where they were supporting Admiral Cunningham’s Eastern Mediterranean Fleet. The new battleship ‘Richelieu’ sailed from Brest to Dakar.

Darlan told the British that the French fleet would never fall into the hands of the Germans. When the French were presented with the Germans terms of surrender they included the instruction that all French warships were to return to harbours in France where they would be disarmed. The German terms stated that the Germans would not use the French ships for their own purposes, with the exception of coastal boats that would be used for mine-sweeping.

The British ambassador at Bordeaux, Sir Ronald Campbell, communicated these terms to London. Churchill went on radio to castigate the French for accepting the Germans terms. However, in the midst of his anger, Churchill was not informed of a last-minute concession made by the Germans on June 22nd. Pétain insisted that disarming the warships had to happen in French African ports – not in France. The Germans agreed to this. On June 23rd, Campbell and his staff left Bordeaux for Britain and he never got to know about this concession. After this, communication between Churchill’s government and the French became patchy at best. The formal agreement to the terms of the surrender occurred on June 30th at Wiesbaden.

The lack of communication between the British and French was to have dire consequences. As early as June 20th, Darlan had sent a coded order to the captains of the warships based in French African ports – do not surrender your ships intact to the Germans. On June 24th, he repeated this order with specific instructions to make preparations to scuttle the ships if it seemed likely that they would be captured. The British were unaware of this instruction and on June 27th the British government took the decision that the French ships could not be allowed to fall into the hands of the Germans and that the Royal Navy would ensure that this would not happen.

On June 28th, Force H was created under the command of Vice-Admiral James Somerville. The flagship for Force H was ‘HMS Hood'; the battleships ‘Resolution’ and ‘Valiant’ and the carrier ‘Ark Royal’ with eleven destroyers made up this force. It was to be based in Gibraltar.

On July 1st, Somerville received his first order as the commander of Force H – “to secure the transfer, surrender or destruction” of the French warships in North Africa. On July 3rd, Force H arrived at Mers el Kébir and the commander of the French ships there, Admiral Gensoul, was given four choices:

1) Join the British fleet and continue to fight the Germans

2) Be escorted to the West Indies or to a British port

3) Have the ships disarmed at Oran under the supervision of the British

4) Scuttle the ships where they were harboured.

If Admiral Gensoul refused to accept any of these choices, Somerville would use force to destroy the ships. However, many senior officers in Force H were wary of using force against a navy that had until recently been fighting on their side. They expressed their reservations to Somerville who, impressed by their arguments and stance, forwarded this information to the Admiralty. He received a reply that the government expected the French ships to be destroyed and that was their “firm intention”.

Tense talks occurred between the French and the British. Gensoul refused to meet the British naval officer – Captain Holland – on his flagship ‘Dunkerque’. However, Holland was informed that the French would not start any action but force would be met with force if the Royal Navy did start to attack Gensoul’s fleet. Matters were made more tense when the British mined the entrance to the harbour at Mers el Kébir using planes from the ‘Ark Royal’. Gensoul kept in contact with Darlan during this stand-off. However, the records show that Gensoul only told Darlan of one of the British ultimatums – that the fleet would be destroyed within six hours – the other choices were never relayed to Darlan. In response to this message, Darlan ordered all other French naval ships in the Mediterranean to steam to Mers el Kébir to assist Gensoul. The Admiralty picked up this message and relayed it to Somerville – that he could shortly expect far more French warships in the area around Oran. This effectively forced Somerville’s hand.

At 18.00 on July 3rd, the British opened fire. The Royal Navy’s ships were in open water and could manoeuvre themselves into a perfect firing position. The French could not do this as they were in the confined space of a harbour. The first ship to be sunk was the battleship ‘Bretagne’. A shell exploded her ammunition and within seconds the ship capsized. 977 men were lost. The ‘Dunkerque’ was also hit and damage to her boiler room took away her power so that she had to drop anchor in harbour. The ‘Provence’ was also hit and was beached by her captain to prevent the ship from sinking with subsequent loss of life. The destroyer ‘Mogador’ was also hit with the loss of 37 men. In the confusion and disguised by the extensive smoke, the battleship ‘Strasbourg’ managed to leave Mers el Kébir and somehow avoided the mines at the harbour entrance.

After a thirteen minute bombardment, Somerville ordered an end to the firing. The ‘Strasbourg’ managed to get the Toulon. Force H returned to Gibraltar. On July 4th, planes from the ‘Ark Royal’ were ordered to return to Mers el Kébir and finish off the ‘Dunkerque’ as it was believed that the ship had only sustained minor damage. The attack led to the deaths of 150 men and put the ‘Dunkerque’ out of action for one year.

An attack by the aircraft carrier ‘Hermes’ on the ‘Richelieu’ at Dakar damaged the new battleship but never put it completely out of action.

Delicate negotiations at Alexandria led to a non-violent settlement whereby the French disarmed their ships and de-fuelled them after Cunningham gave his word that no force would be used against men who had worked so well with the British fleet under his command in the Eastern Mediterranean.

At Plymouth and Portsmouth, armed British sailors took over the French ships that were harboured there. In the struggle to take control of the submarine ‘Surcouf’ a French officer was killed and two British officers were wounded. The French crews were interned in the Isle of Man or in a camp near Liverpool.

Was ‘Operation Catapult’ a success? A number of large French warships were destroyed and did not fall into the hands of the Germans. Whether they would have tilted the naval balance towards the side of the Germans will never be known as when the Germans entered the port of Toulon, where the surviving French warships were harboured, the French scuttled them.

The great damage done was to French/British relations. In late May 1940, the French and British navies had been comrades-in-arms during Dunkirk. Just weeks later, over 1000 of the French sailors who had served at Dunkirk were dead – killed during Operation Catapult. Many in France found this hard to take or accept and it has been argued that it encouraged some French people to collaborate with the Germans, though the evidence for this is hard to gather. The internment of sailors who had sailed to Britian at the request of the British government was another source of great anger. To others, it showed that the British would be resolute and heartless in its attempt to stop the German military steamrolling over all of Western Europe and that ‘Operation Catapult’ was just one part of this resolute approach.